By: Dheeraj Gupta Koona - Senior Sustainability Consultant, KSA

Date Published: January 30, 2026

Smart cities and net-zero buildings are redefining how energy is generated, managed, and consumed within the built environment. As urban areas increasingly integrate digital technologies and Internet of Things (IoT) systems, the demand for decentralized, low‑carbon energy solutions continues to grow, as highlighted by the International Energy Agency’s Buildings Global Status Report. While mainstream renewables such as solar photovoltaics and wind energy remain central to decarbonization strategies, energy harvesting technologies offer complementary opportunities to capture ambient energy embedded within everyday urban activity.

Piezoelectric energy harvesting converts mechanical stress from footfall, vehicular movement, and structural vibration into electrical energy. Although not intended for large-scale power generation, piezoelectric systems can play a strategic role in sustainable urban infrastructure by supporting self-powered sensors, reducing battery dependence, and improving the resilience of IoT-enabled systems. This article explores the applicability of piezoelectric energy harvesting in buildings, campuses, and mobility infrastructure, drawing on global case studies to evaluate performance, sustainability implications, and practical limitations.

Smart cities are increasingly defined by their ability to integrate sustainable urban infrastructure with digital intelligence. Buildings and transport systems account for a significant share of global energy consumption, positioning net-zero buildings as a cornerstone of climate action strategies, according to analysis by the International Energy Agency. At the same time, IoT deployment in the built environment is accelerating, with sensors, monitoring systems, and connected assets becoming standard features of modern developments.

This convergence of sustainability and digitalization has intensified the need for decentralized energy solutions capable of powering low-energy devices reliably and with minimal maintenance. Conventional centralized power systems and battery-dependent sensors can introduce operational and environmental burdens at scale. Piezoelectric energy harvesting offers a complementary approach by converting mechanical energy already present in urban environments into usable electrical power, enabling localized and resilient smart infrastructure.

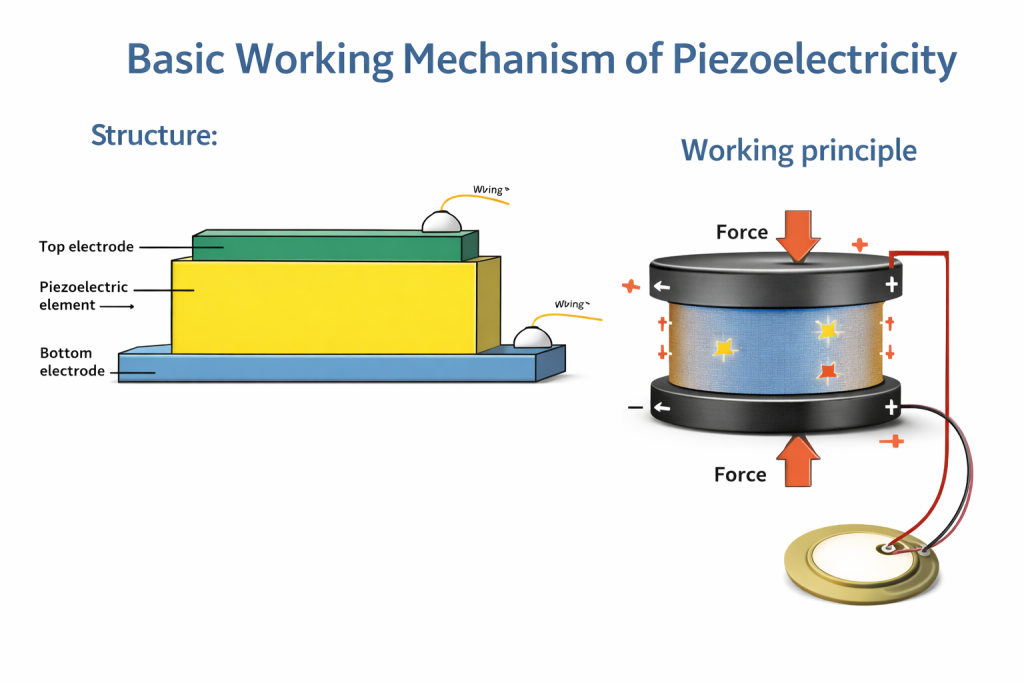

Piezoelectric materials generate an electrical charge when subjected to mechanical stress such as compression, bending, or vibration, a phenomenon extensively described in the smart materials literature by Anton and Sodano. This principle has long been applied in sensors and actuators, while energy harvesting applications focus on capturing small amounts of power from repetitive mechanical events.

Within buildings and infrastructure, these events include pedestrian movement, vehicular loads, and vibrations from mechanical systems. The generated electricity is typically conditioned, stored in capacitors or small batteries, and used to power low-energy devices such as wireless sensors and communication nodes. Research summarized by Stanford University indicates that piezoelectric harvesting is best suited to environments where vibration or loading is frequent, predictable, and aligned with low-power demand.

Figure 2. Schematic of piezoelectric energy conversion from mechanical stress to electrical output

Material selection plays a critical role in determining the efficiency and sustainability of piezoelectric systems. Lead zirconate titanate (PZT) ceramics provide high energy conversion efficiency but raise concerns regarding toxicity and end-of-life management, as discussed in Priya and Inman’s work on energy harvesting technologies. Polymer-based materials such as polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) enable flexible integration into floors and building elements but offer lower energy density.

Emerging lead-free ceramics seek to balance performance with environmental responsibility, aligning more closely with ESG objectives. Beyond materials, system design must address durability under repetitive loading, electrical conditioning, integration with energy storage, and seamless connectivity with IoT platforms. Long-term reliability is particularly critical for installations embedded in floors, pavements, or road infrastructure.

Smart buildings and campuses represent the most viable environments for piezoelectric energy harvesting due to predictable footfall patterns and controlled operating conditions. High-traffic areas such as entrances, corridors, transit interfaces, and university campuses can generate sufficient mechanical energy to support localized applications.

Typical use cases include self-powered occupancy sensors, environmental monitoring devices, wayfinding systems, interactive displays, and data collection nodes. In net-zero developments, piezoelectric systems complement broader energy strategies by enhancing operational efficiency and reducing reliance on batteries and wired connections rather than contributing meaningfully to bulk energy supply.

Figure 3. Applications of piezoelectric harvesting across smart buildings and campuses.

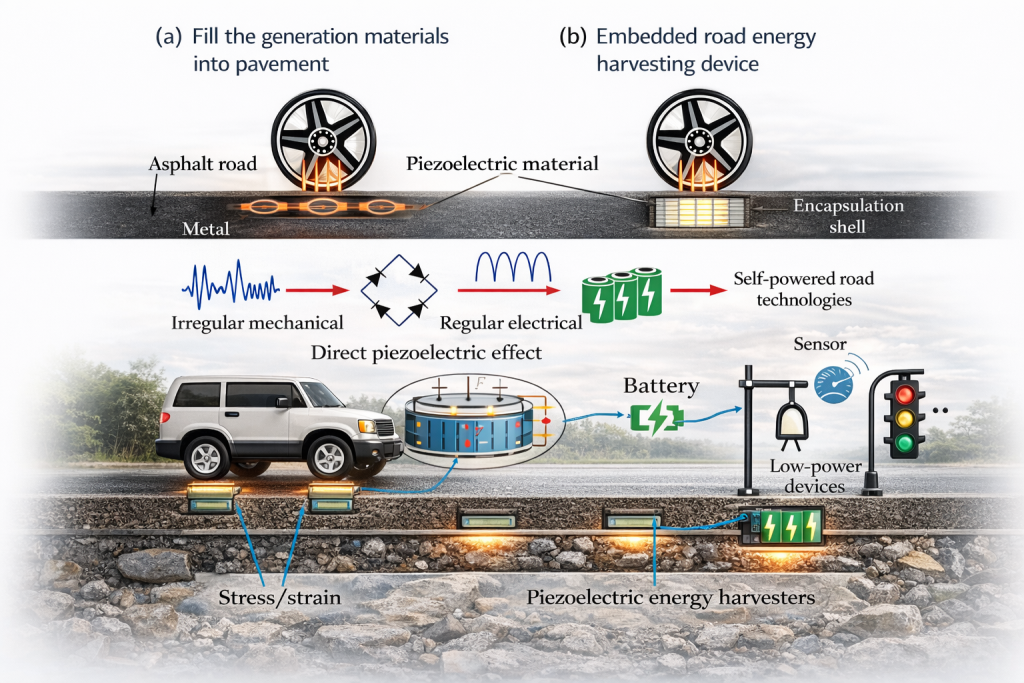

Urban mobility infrastructure—such as roads, parking facilities, and logistics hubs—has also been explored for piezoelectric energy harvesting. Vehicular load applications involve higher mechanical forces than pedestrian systems, offering theoretical potential for greater energy capture.

Pilot projects reported by the California Energy Commission demonstrate that embedding piezoelectric generators beneath road surfaces demonstrate technical feasibility for powering localized infrastructure such as traffic sensors and low-power lighting. However, installation complexity, durability challenges under heavy vehicles, and limited energy yield have constrained large-scale deployment. As a result, mobility-based applications are best suited to targeted or demonstrative roles within smart city programs.

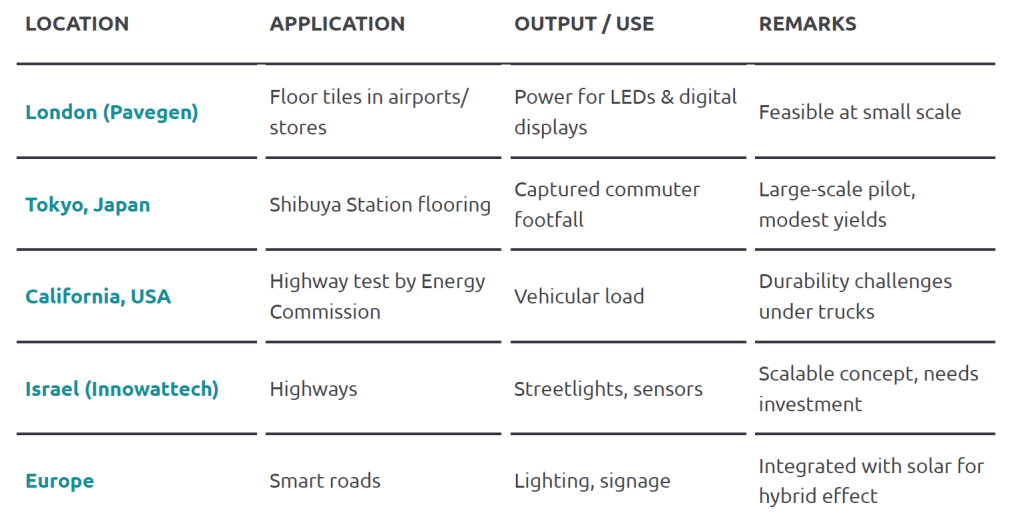

Real-world deployments provide valuable insight into the performance, scalability, and limitations of piezoelectric energy harvesting. While most projects remain at pilot or demonstrator scale, they offer important lessons for smart cities and net-zero developments.

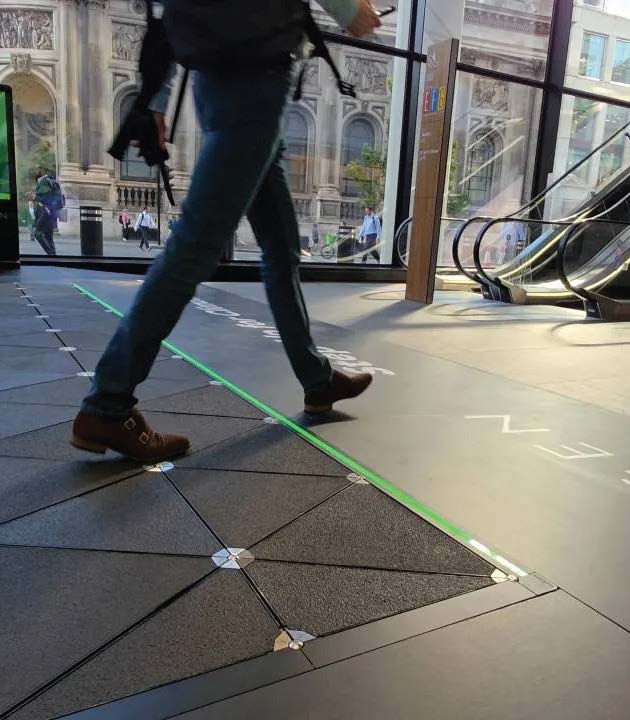

In the United Kingdom, piezoelectric energy harvesting has been most visibly deployed through Pavegen’s kinetic flooring systems installed in airports, retail environments, transport hubs, and educational campuses. According to Pavegen Technology and Case Studies, these systems are typically located in high-footfall areas where pedestrian movement provides a consistent mechanical energy source.

The harvested energy is used to power LED lighting, digital displays, and interactive installations, often combined with analytics platforms that visualize pedestrian movement. While absolute energy output is modest, these projects demonstrate strong feasibility for localized, low-power applications and deliver significant value in public engagement and sustainability visibility.

Figure 4. Pavegen kinetic flooring in a public transport environment

Japan has explored piezoelectric energy harvesting within one of the world’s busiest urban transport environments. A widely reported demonstration at Shibuya Station in Tokyo involved piezoelectric tiles installed to capture energy from commuter footfall, as documented by Parametric Architecture, Technrok, and OHEPIC.

The system converts mechanical pressure from footsteps into electrical energy, which was stored and used to power localized applications such as LED displays and experimental lighting. Reports indicate that individual footsteps generate very small amounts of electricity, but the exceptionally high pedestrian volumes at Shibuya enable meaningful cumulative output for low-power uses.

Publicly available long-term performance data and detailed economic metrics remain limited. The project is nevertheless instructive, illustrating both the potential and the constraints of footfall-based energy harvesting in dense urban environments, and reinforcing the importance of realistic expectations regarding energy contribution.

Figure 5. Conceptual illustration of piezoelectric tiles at Shibuya Station

In the United States, pilot projects—particularly in California—have investigated piezoelectric generators embedded beneath road surfaces to harvest energy from vehicular loads. Findings published through state energy research programs show that electricity can be generated from traffic-induced stress but also reveal significant durability and cost challenges.

Energy yields have generally been insufficient to justify widespread deployment, especially under heavy truck traffic. These findings reinforce the view that road-based piezoelectric systems are better suited to powering localized sensors or monitoring equipment rather than contributing meaningfully to grid-scale energy supply.

Figure 6. Road-embedded piezoelectric energy harvesting concept

Israel-based company Innowattech has conducted some of the most extensively documented trials of piezoelectric energy harvesting in highway environments. Innowattech reports describe systems embed piezoelectric sensors within roadways to capture energy from passing vehicles, directing output toward street lighting, traffic monitoring sensors, and communication systems.

These projects demonstrate a multi-functional approach, combining energy harvesting with sensing and data collection. While scalability has been demonstrated conceptually, long-term deployment depends on sustained investment, supportive policy frameworks, and continued performance monitoring.

Figure 7. Innowattech piezoelectric highway system schematic

Several European pilot projects, particularly in Italy and the Netherlands, have explored hybrid smart road concepts that combine piezoelectric elements with solar photovoltaics, as documented through research and project reporting published by the European Commission’s CORDIS platform. In these systems, piezoelectric components typically support auxiliary functions such as sensors or signage, while solar panels provide the primary energy input.

This hybrid approach improves overall system viability and underscores a key lesson for sustainable urban infrastructure: piezoelectric energy harvesting is most effective when integrated within broader, multi-technology energy strategies.

Across regions and applications, several consistent insights emerge:

These findings position piezoelectricity as a complementary technology within smart cities and net-zero developments rather than a standalone energy solution.

From an ESG perspective, piezoelectric energy harvesting contributes primarily by supporting decentralized digital infrastructure rather than bulk energy generation. Its strengths lie in resilience, innovation signaling, and alignment with smart city narratives centered on climate action and technological leadership.

Lifecycle considerations—including embodied carbon, material toxicity, durability, and end-of-life management—are essential to ensure genuine sustainability outcomes and avoid overstating environmental benefits.

Despite growing interest, piezoelectric energy harvesting faces clear limitations. Energy output remains low, economic returns are uncertain, and standardized design guidance is limited.

Transparent communication of these constraints is essential to maintaining credibility in net-zero and smart city strategies.

Future research and innovation can strengthen the role of piezoelectricity in sustainable infrastructure through:

By aligning piezoelectric innovation with global sustainability goals, the built environment can diversify its renewable energy portfolio and unlock new pathways for decarbonization.

Piezoelectricity represents a promising frontier for sustainable construction and infrastructure. While unlikely to replace mainstream renewables, its niche applications in high-footfall and high-traffic environments offer tangible opportunities for localized energy harvesting. When deployed strategically and transparently, piezoelectric systems can support self-powered IoT infrastructure and enhance the resilience of smart, net-zero developments.

Senior Sustainability Consultant

KSA

Dheeraj is a Senior Sustainability Consultant at AESG, with over 13 years of experience as a Building Science Engineer, specializing in sustainable design and climate action. He is a USGBC faculty, LEED SME and holds key sustainability credentials, including LEED AP, WELL AP, Envision SP, Parksmart Advisor, Activescore+Modescore AP, ISO 14064 GHG Lead Verifier/Validator and ISO 14001 Lead Auditor. His expertise spans sustainable engineering, energy conservation, and integrated building design.

He leverages a cross-functional background and a holistic approach to develop effective sustainability strategies for the built environment and guides clients in achieving their Sustainability goals and certifications.

For further information relating to specialist consultancy engineering services, feel free to contact us directly via info@aesg.com

ISO 27001:2022

ISO 9001:2015

ISO 14001:2015

ISO 45001:2018

601-608

The offices at Ibn Battuta Gate,

Jebel Ali 1-Village

PO Box 2556

Dubai, United Arab Emirates

305 Mermaid House

2 Puddle Dock

London, EC4V 3DS

United Kingdom

T / +44 (0) 208 037 8762

Haibu Space, Abu Dhabi Mall

1st floor, Office 37

Tourist Club Area

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

T / +971 (0) 2 201 2527

9391 Wadi Al Thummamah

2444 Al Olaya District

PO Box 12214

Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

T / +966 (0) 112 278 288

111 Somerset Road

#08-10A, 111 Somerset

Singapore 238164

11th Floor, Office 1101

2 Long Street

Cape Town 8000

Western Cape, South Africa

T / +27 (0) 21 137 6444

8 Parramatta Square

49th Floor, Office 117

Parramatta, Sydney

New South Wales 2150

Australia

T / +61 (0) 2 8042 6817

Regus Rialto, West Podium

Level Mezzanine 2 (M2)

525 Collins Street

Melbourne, Victoria 3000

Australia

Regus Egypt, East Lane

1st Floor, Office 130

Plot number B-340

New Cairo 1

Cairo Governorate 4740003

Egypt

Office 37, Haibu Space

1st floor, Abu Dhabi Mall

Tourist Club Area

Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

T / +971 (0) 2 201 2500

9391 Wadi Al Thummamah

2444 Al Olaya District

PO Box 12214

Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

T / +966 (0) 112 278 288

111 Somerset Road

#08-10A, 111 Somerset

Singapore 238164

11th Floor, Office 1101

2 Long Street

Cape Town 8000

Western Cape, South Africa

T / +27 21 137 6444

49th Floor, Office No.117

8 Parramatta Square

Parramatta, Sydney

New South Wales 2150

Australia

T / +61 (0) 2 8042 6817

Regus Rialto, West Podium

Level Mezzanine 2 (M2)

525 Collins Street

Melbourne, Victoria 3000

Australia

Enawalks, 4th Floor, Office 417

Leaders International College Road

2F97+6VJ New Cairo 1

Cairo Governorate 4724242

Egypt

T / +20 15 01692187

Copyright 2026 | AESG | All Rights Reserved