Introduction

Approved Document O came into effect on 15 June 2022 and applies to all new build dwellings (houses and flats), care homes and student accommodation (for students aged 5 years and over, e.g. inc. boarding schools).

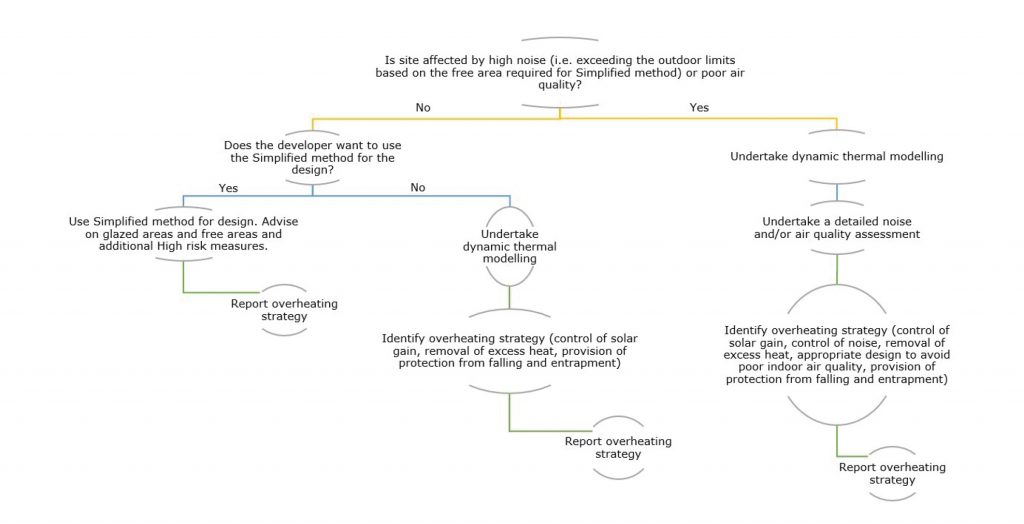

The law and accompanying statutory guidance when read as a whole means that the noise and air quality exposure on a site are extremely important factors, dictating the subsequent route that can be taken to develop an overheating strategy.

In fact, the following decision tree applies when designing to the guidance:

However, there is an incredible amount of ambiguity in the regulation, particularly when it comes to the precise requirements of the noise and air quality statutory guidance.

There are clear objective parameters, but there are also clear gaps, including competency of an assessor and the approach that should be taken. Because of the ambiguity throughout the document, people are naturally questioning various aspects, and there is an air of confusion on the application of the regulation.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that the ethos (and law) of the regulation stands true:

Living accommodation should be fit for purpose and limit unwanted solar gain, provide an adequate means to remove heat, whilst accounting for the safety of the occupant and their reasonable enjoyment of the residence.

Indeed, it’s possible, with reasonable assumptions, to produce an overheating strategy that reflects the legal requirements and which can be considered compliant with the regulation.

Step 1 – Early Site Risk Assessment

Once you know where the site is going, the first thing you need to do is commission a noise and air quality assessment. These assessments should follow appropriate procedures to be reliable and robust. The results of these studies need to show the exposure across the site.

To determine whether the Simplified method can be used, the below limits (in free field conditions) cannot be exceeded:

| High risk location | Moderate risk location | |

|---|---|---|

| LAeq.8h average across 8 hours (between 11pm and 7am) | 44 dB | 49 dB |

| LAeq.8h more than 10 times a night (between 11pm and 7am) | 59 dB | 64 dB |

The government faq’s associated with Approved Document O crucially confirm that the only location needing to use the High risk measures is London. Although central Manchester is listed as being at risk of elevated night-time temperatures, you are still only required to follow the Moderate risk measures, with consideration of following the High risk measures only optional.

To put these noise levels into context, 22% of the UK population were deemed to be subject to noise in excess of the average noise limit when the government last considered exposure (National Noise Incidence Study, 2000). Additionally, the same study found that the average noise level in London at night was 50 dBA, and this is likely to be the same as most city centres across the country. Furthermore, the maximum noise limits are likely to be exceeded with 10 car passes within 10-20m of a bedroom window.

For air quality, Approved Document O points to Section 2 of Approved Document F. This then leads to a requirement to identify whether the legal limits for exposure to poor air quality will be exceeded. Although not expressly stated, this is likely to be interpreted as meaning you cannot use a natural opening (e.g. an open window) as part of the overheating strategy when the openings face poor air quality. However, most sites outside of city centres are typically bounded by a road or rail line, and any dwellings away from sources of noise or poor air quality are likely to be able to use an open window. Therefore, it is likely that most sites will contain a portion of dwellings where an open window cannot be used and a portion where it can.

Commissioning an early risk assessment is, therefore, essential, as this will define what strategy is possible and will consequently feed into the cost of construction and land viability.

Step 2 – Dynamic Thermal Modelling (if required)

For any areas of a building / site that are predicted to exceed these limits, a dynamic thermal model needs to be commissioned. In the interests of energy saving and sustainable design, it is important that heat gains are reduced as much as possible, so that when heat is needed to be removed, it can be done using passive methods. Crucially, another clarification in the faq’s associated with Approved Document O confirms that if using mechanical ventilation for cooling at night, the home can still be considered to be predominantly naturally ventilated, which is helpful for dynamic thermal modelling.

The regulation requires the exploration of all passive means (inc. using mechanical ventilation to remove heat) before opting for air conditioning. The following hierarchical approach to removing excess heat is recommended in the regulation:

In order to effectively do this, the dynamic thermal model needs to produce a solution that is just compliant, and not just assume windows are fully open with a comfortable pass, as this will inevitably lead to a greater use of mechanical systems.

Step 3 – Ensuring the Overheating Strategy is Usable

Where air quality limits are identified as potentially being exceeded or noise levels prevent the use of an open window, the extent of exposure should be confirmed by detailed studies.

The noise consultant needs to receive information on facade openings and any ventilation rates to design the noise control solution.

This then presents the following hierarchical approach to defining noise mitigation such that the overheating strategy is usable:

| Degree of noise control | Solution to remove excess heat |

|---|---|

Low | Open window |

| Moderate | Louvred façade to the equivalent area of the open window. A partially open window may reduce the area required from the louvre. |

| High | Closed window and a mechanical ventilation system, with sufficient make-un air via vents in the facade |

| Very High | Closed window with no facade openings and cooling via a centralised system or air conditioning |

Due to the areas needed to provide a natural means for removing excess, the opportunity to use ventilation louvres alone is typically small due to the practical constraints resulting from the air resistance of the louvre coupled with the size needed to sufficiently remove heat. However, an acoustic louvre does extend the upper noise level before a mechanical system is needed. Additional measures such as balconies can further extend the viability of a natural solution.

The majority of sites outside of areas subject to the urban heat island effect (e.g. outside London, Manchester, Southampton and Birmingham) are likely to be able to use a mechanical ventilation solution, albeit at considerably higher ventilation rates than common for background ventilation. Given it is more cost effective to use a decentralised system and given the ventilation rates needed, provision for make-up air within the room being served by the system will likely be required.

Where air quality is established to be in excess of the limits, the means of removing excess heat is likely to be limited to closed windows and no direct facade openings, and any mechanical ventilation system will need to be fitted with appropriate filters.

Step 4 – Defining the Overheating Strategy

The results from Step 3 can then be communicated to the client / design team and refined as needed. The developer is required to submit a modelling report to Building Control when using dynamic thermal modelling. This report should contain the details in CIBSE’s TM59, section 2.3 and the compliance checklist in Appendix B of Approved Document O should also be provided to the building control body. Given the statutory guidance in the regulation, any solution within the submitted report should be usable and, thus, should have accounted for noise and air quality exposure.

Furthermore, in order to answer the checklist question ‘Are there any security, noise or pollution issues’ and given the significant complexity embedded in any response, evidence from a competent person to support the response is recommended. This could be either submitted alongside the dynamic thermal modelling report or at least have on file to produce if requested. It is also crucial to document the solution in order that the design can be effectively implemented during construction.

Other Points to Note

We (the co-authors of the Acoustics, Ventilation and Overheating Guide) have drafted guidance on the use of the regulation to help clarify any ambiguity and provide a method for compliance. I have summarised approaches in this article but the guidance should be used to ensure a robust and reliable strategy. There is a lack of good, correct data available from suppliers, which limits available options. There are large assumptions built into things like the air movement via an open window and the exact acoustic performance of likely products at a given aerodynamic situation. This will inevitably lead to questions over the effectiveness of any solution once built.

Some people have wondered what will happen when our road vehicles are all driven by non-combustion engines. The answer is, it will likely reduce noise in urban areas, where road speeds are 30 mph or less, but where vehicles are travelling at higher speeds, tyre noise dominates which won’t change.

In paragraph 3.2, Approved Document O says ‘in locations where external noise may be an issue (for example, where the local planning authority considered external noise to be an issue at the planning stage), the overheating mitigation strategy should take account of the likelihood that windows will be closed during sleeping hours’. This doesn’t mean that only if the local planning authority considered external noise to be an issue, do you consider noise as part of the overheating strategy.

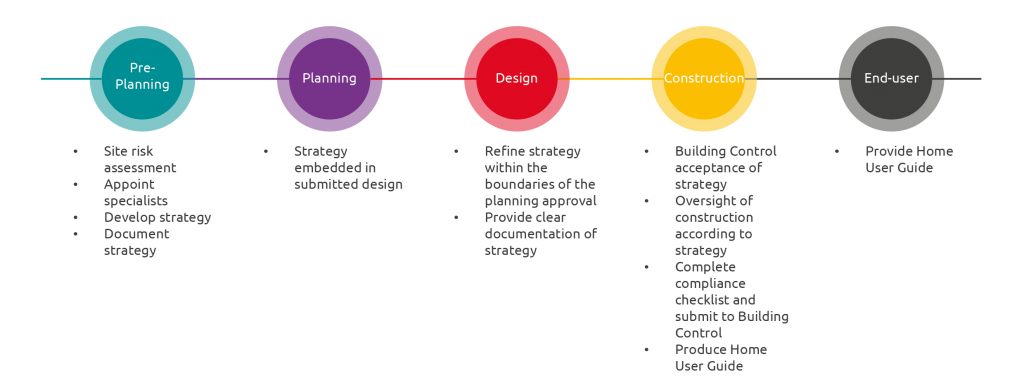

The way I see it, the thread to compliance is as set out below. This will require early engagement with specialists, prior to any planning application, so that the scheme approved at the planning stage can be built according to Building Regulations.

Summary

Despite the confusion surrounding the application of Approved Document O, the ethos of the regulation is clear and there is a method that can be used to enable effective use.

The steps to an assessment comprise:

Most importantly, make sure you have competent people developing your strategy to avoid taking on unknown risks.

How can AESG help?

AESG is a specialist consultancy, engineering and advisory firm headquartered in London, Dubai, Riyadh and Singapore working on projects throughout Europe, Asia and Middle East. We pride ourselves as industry leaders in each of the services that we offer.

We have one of the largest dedicated teams with decades of cumulative experience in sustainable design, fire and life safety, façade engineering, building commissioning & digital asset management, waste management, environmental consultancy, strategy and advisory, acoustics, and carbon management.

Director of Acoustics, UK

James Healey is a Director of Acoustics in our AESG UK team. With a first class honours B.Sc Acoustics, he has over 17 years of extensive experience in the field of acoustics including working at the Building Research Establishment (BRE).

He is also the Chairman of the UK Institute of Acoustics (IOA) Building Acoustics Group and is a co-author of the UK national guidance document on Acoustics, Ventilation and Overheating.

As a leading expert in the assessment of ventilation and overheating within buildings and in acoustic sustainable design, he has worked on a wide range of projects across sectors both in the UK and internationally.

With his passion and technical leadership he looks forward to supporting and advising clients on their acoustic consultancy needs.

For further information relating to specialist consultancy engineering services, feel free to contact us